I don’t remember how I came across this book – could have been through Gastropod? – but I thought it sounded like just my thing. Time as an ingredient makes a lot of sense, when you consider it! And overall, Linford does look at some interesting points in connecting food with time; I learned a few things and was encouraged in my love of cooking and food.

I don’t remember how I came across this book – could have been through Gastropod? – but I thought it sounded like just my thing. Time as an ingredient makes a lot of sense, when you consider it! And overall, Linford does look at some interesting points in connecting food with time; I learned a few things and was encouraged in my love of cooking and food.

However, this book turned out to be not quite what I expected. On reflection, I think I was expecting something more like Michael Pollan’s Cooked, where he meditates on particular ways in which fire or air or whatever have an impact on cooking and food at length. This is not that. Instead, this is a long series of vignettes. Some of them do go over pages – there’s a good few pages on pickles, and on smoking, and the wonders of freezing., among others. But in general each topic within each timeframe (seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years) is relatively short, addressing the connection between the topic and time – the seconds between different stages of caramel, the time it takes to make true traditional Modena balsamic vinegar – and usually not going into the depth that my heart really wanted. (And sometimes the topics chosen in each chapter seem to be tangential to the concept of time as an ingredient, but maybe I missed the point.)

If what you’re interested in is a series of short stories about time and cooking, that you can easily dip into and out of, that are sometimes amusing and sometimes poignant and that remind you that cooking and good food are good things, then you will probably enjoy this book.

This book was recommended to me by

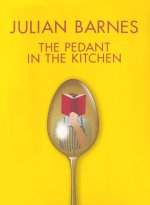

This book was recommended to me by  My beloved, loving, and never at all snarky mother gave me this book a couple of years ago, for my birthday I think. I was a little miffed at the time, although that didn’t stop me enjoying it. I’ve just re-read it, and once again I really appreciated it. In fact, I think I got more out of it on this read-through.

My beloved, loving, and never at all snarky mother gave me this book a couple of years ago, for my birthday I think. I was a little miffed at the time, although that didn’t stop me enjoying it. I’ve just re-read it, and once again I really appreciated it. In fact, I think I got more out of it on this read-through. When I

When I